Growing up in the Tsum Valley

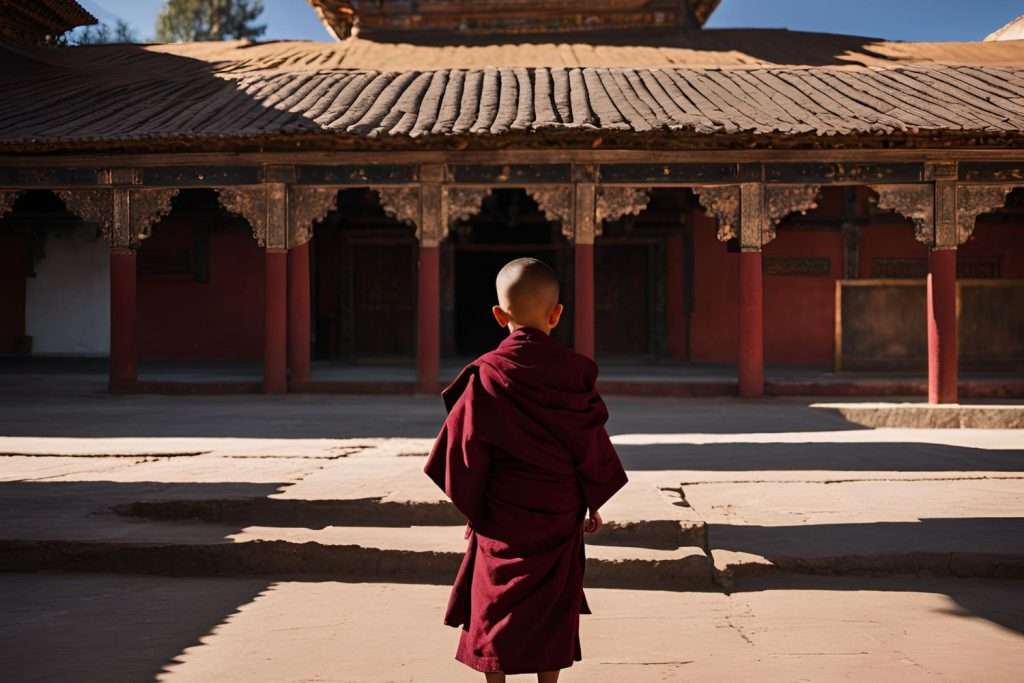

I was born in the Himalayan region, right on the border of Tibet and Nepal, in Tsum Valley or Happy Valley. It is said that there is hidden Dharma treasure here, buried underground, in stupas, and in the atmosphere. For thousands of years, many masters have mediated there, like Milarepa.

Before, the village was a restricted area and quite isolated, but about eight years ago it opened for outsiders to visit. It is a very humble village, but whoever travels there finds extraordinary peace. They fall in love immediately.

It is a very humble village, but whoever travels there finds extraordinary peace.

I was born there in 1975, the oldest of seven children. My mother had a difficult birth with me, I was told that I was coming out the opposite way—usually, the head comes first—and over there all births are natural births. My feet came first, and then I was halfway stuck.

A meditator in the cave—who came from Tibet and settled there, to whom my family had a spiritual connection—suddenly appeared at my home, as if he knew what was going on. The moment he saw what was happening, he asked my aunties to get butter. I think I was born in January, in the middle of winter, because the butter was very hard. He blessed the butter and asked my mom to swallowed it.

The moment she swallowed it, my body naturally pushed back in, and within less than a minute I did a U-turn and came out. That was my first spiritual contact to my master—in this lifetime—who I regard as my guru. His name is Geshe Lama Konchog; he is in the documentary Unmistaken Child. When I first came into the world, I put my mother and myself in danger and my master saved us. That was my first exposure to the world.

Then I had a quite tough childhood. By four I had to look after the cows, and collect wood and cow dung which we would dry and use for the fire. All my siblings were about two years apart. By then I had two brothers and you could see my face didn’t look like any of my family members.

By four I had to look after the cows, and collect wood and cow dung which we would dry and use for the fire.

Even before that, when I was born, I was told my face was so ugly that my family didn’t even show me to the other villagers. When you’re born, about after a week, people in the village will come visit and congratulate you, wanting to see the baby’s face. I was told I looked like a worm.

When I was born, I was told my face was so ugly that my family didn’t even show me to the other villagers.

Then I evolved, but I still didn’t look like any of my family members. In that very small village friends would tease my father saying it seemed like I was not his boy. Since it’s a very small village and people are narrow-minded, he started to think I wasn’t his son. He started to have a bit of an aversion to me.

My brother is like a copy of my father’s face, and he was the favorite. Since I was little, I longed for a hug, I always longed for kind words from my father. My mother was very loving to me, and the rest of my family was very loving to me. But my father would give them obstacles to express that love openly.

Whatever expressions of love that I got from my mother was when my father wasn’t around. As a little baby, I had a hunger for love, for a hug, especially when I’d see my brothers always put on my father’s lap, and he’d pet them. There was jealousy.

Whenever he talked to me, it was scolding, like something was wrong with me. There was no sympathy for me at the age of four, I had to go work, collect firewood, and look after the cows. But during that time, fortunately, my master was still in the cave, and somehow—without people telling me how precious he is—my mind was full of him.

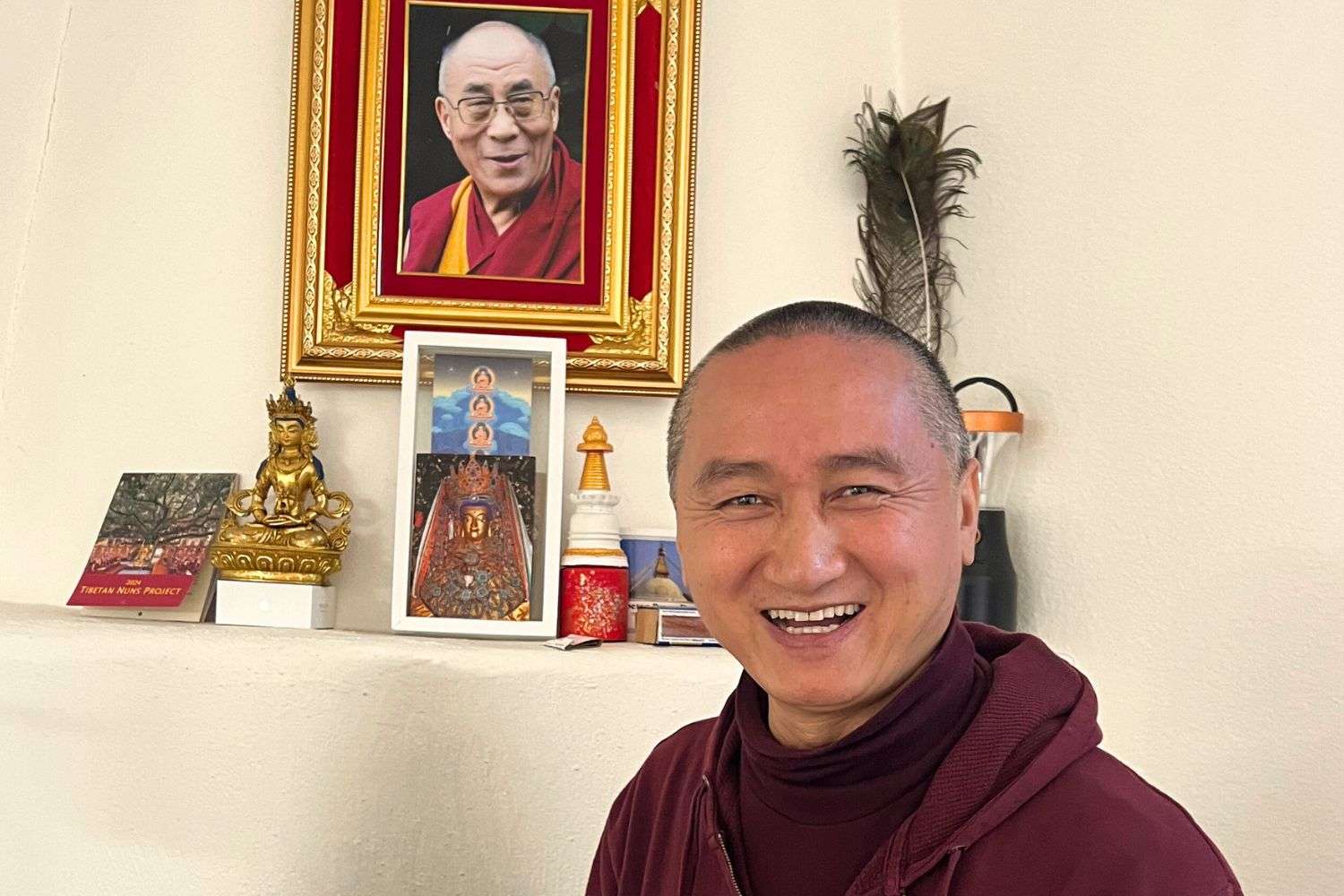

Geshe Lama Konchog

The journey to his cave took about an hour and it was straight uphill. I would just go. But I couldn’t stay too long because if my father didn’t see me at a certain time, I’d get into trouble again. He had a big cot, and he hardly talked. I used to go in there and fall asleep immediately, the most peaceful time, and I experienced physical warmth. Mentally, I felt protected too, and I finally had the chance to rest or sleep.

Sometimes one of my family members would come to take me away. Then my master would say, You better go back. Along the way, my whole body would get scratches, passing through the bushes. My life was very much like that until the age 7, when I started to follow my father when he’d do business, he’d trade and collect herbs for incense or medicine from the mountains, then he’d go to Kathmandu which takes 16–19 days walking from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m.

He’d have to carry all of the herbs by himself before I turned seven. I don’t know how he carried everything, food and supplies, but when I started traveling with him, it was mainly to carry the food supply. I’d help him carry spelt flour or barley flour for food. Because we didn’t have money for food for restaurants. This flour would be our breakfast, lunch, and dinner every single day. We’d carry one wooden bowl and scoop two or three spoons of water from a waterfall or river and make it into a drink.

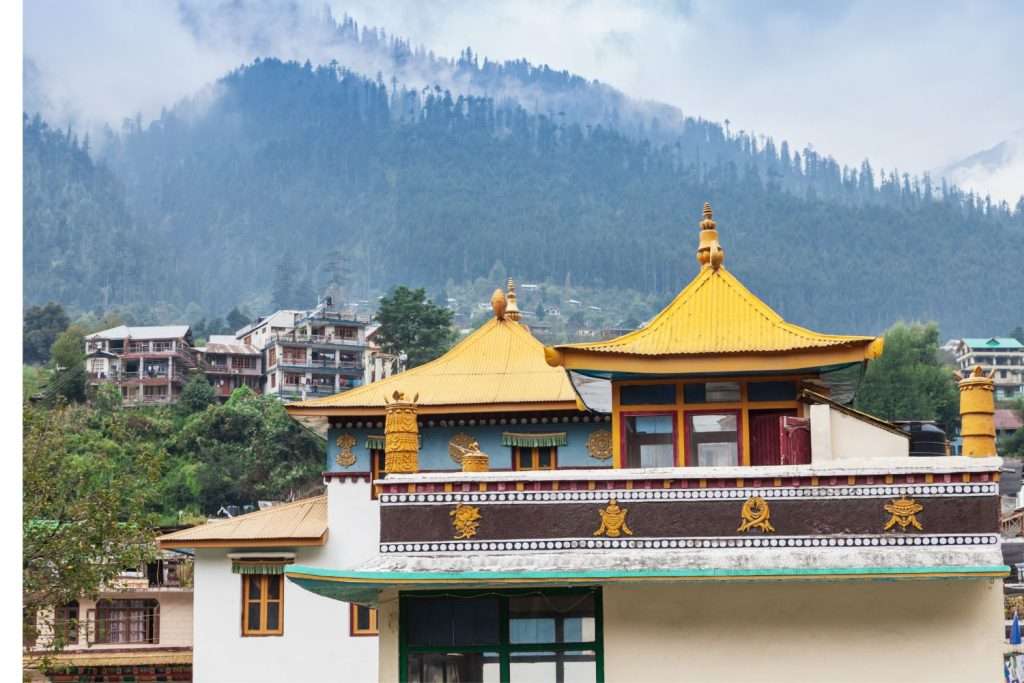

When we reached Kathmandu we didn’t have a place to go, we mostly went to one stupa (Kathesimbu), right in the middle of the city, next to Thamel, the center of the tourist area. That stupa used to be my home when we’d come down to Kathmandu, it is believed to hold relics of Buddha Kassapa, one of the fortunate Buddha who already came to this world.

Around the stupa there weren’t many shops, but lots of houses and sheds. In Nepal, they go inside quite early on and stay inside. My father and I used to find a space and sleep there, then in the early morning we’d display the herbs and hope someone would come and buy them. Or we’d walk around and exchange, usually for rice and sugar.

One of the main purposes was to get rice and sugar and if there was extra money then we would buy some threads, needles, shoes, or something for the family. And in fact, this rice and sugar was not for the family to eat. Once a year our family would invite 15-20 nuns and monks from the local monastery and nunnery to perform Tara Puja, and during that time they’d make a rice meal for them and sweet tea.

At that time, in my village, rice and sugar was more rare and precious than gold. Most women would wear gold, but rice cost money while gold was passed down. If you had the chance to eat rice, it meant you were rich, it was that precious.

At that time, in my village, rice and sugar was more rare and precious than gold.

I was a porter for three years, from age seven to nine. I found life to be very miserable. I didn’t have shoes, it was very cold at home, and Kathmandu was too hot. There were many mountains to cross and we had to walk nonstop. I was carrying 10 kilos at the age of seven, that’s a full supply. Since my relationship with my dad was not so good, I couldn’t express my misery, or he would scold me.

By nature, he was not a bad person, I think he was suffering a lot. He had to take care of so many family members. My mother got a lot of scolding from him. But it was mainly to me, he was just pouring his own stress to me. As a young boy, I saw him as kind of a monster, he was like the worst person in the world.

Then, when I was around seven, my master disappeared. In my family, everyone acted like he was dead. Every opportunity I’d have, I’d go up to the cave and see if he was there, but he never was. I asked my other family members, and while they didn’t answer me, they acted as if he was no more. In actuality, my father had told the rest of the family that they couldn’t tell me that my master had left for Kopan.

But I had a deep feeling that he was alive. Finally, when I couldn’t take it anymore, I asked my father, Where’s Grandpa Lama? I thought he was a family member. He never answered, he would scold and ignore me. At nine, on my last trip as a porter, I told my father that I strongly felt Grandpa Lama was not dead, and that he knew where he was, and if he didn’t let me see him, I’d kill myself. I would jump from the cliff. My father truly believed me, and I think I really meant it as well.

At the time I had lots of suicidal thoughts, I really wanted to jump from the cliff. The roads were very scary with lots of cliffs and in every sense you would feel so much pain—you were walking on all the pokey rocks without shoes, your head hurting from carrying the heavy load, and emotionally you felt discarded, ignored, and unloved.

At the time I had lots of suicidal thoughts, I really wanted to jump from the cliff.

Suddenly, within one or two hours, he brought my Grandpa Lama. It was like seeing a loving grandpa, and I jumped on him and said, I’m not going away from you. My father is not from the local village, he is from Tibet, he was in the army and a bodyguard for the Dalai Lama. His hometown was by the border, so he had either returned home or was sent to cross the border and then got stuck in the village where I grew up.

There’s a great possibility that my father knew Geshe Lama Konchog even before coming to the village. The reason for that is Lama Konchog left Lhasa, his monastery, Sera Jey, before the Chinese army arrived in Lhasa, he has this dream, vision—he can predict a lot of things—that the Chinese army was about to arrive, and he told people, We better escape, otherwise we will get into trouble. But none of them believed him.

So he left. He walked through the mountains to the border in about three months. At Lhodrak, there’s a central holy place of Milarepa, where Milarepa grew up and met his teacher, Marpa. My father’s hometown was actually nearby, and Lama Konchog disappeared during that period, he must have done retreat in Milarepa’s cave.

When Lama Konchog came to my village, he completed isolated himself, for another 26 years in a cave. About 10 years into his 26 years of retreat, finally, villagers began to become aware of his existence. Even though people had known of his existence, but they saw him not as a mountain monkey or some stranger animal.

He went through hard times because the villagers would use a slingshot and chase him. But that gave him the opportunity to express his spiritual abilities, like quick feet. He could run without even touching the ground, and he could even fly. 15 men found him in his first cave and they thought he was some kind of monkey or bad thing, and they tried to chase him, then they saw him cross over the mountain, that no human could climb, as if he was flying.

He could run without even touching the ground, and he could even fly.

I think this is true, because 15 people all see this. Also, in our scripture, there are yogi-conducive conditions that help you succeed in meditation, in whatever conditions. One of them is quick feet, so you don’t need bridges or roads, whenever they see a place that is suitable for their practice they can just arrive there. There’s no roads, cars, airplanes, but they reached all of these places, how is that possible? They must have used quick feet.

Another yogi-conducive condition is being able to control the elements, controlling hot and cold. You can even stay without shelter, in maybe minus 40 degrees. I think Lama Konchog actually stayed like that in the snow region. Another yogi conducive condition is called Chulen, like extracting nutrition from medicinal substances or blessing a stone with a mantra and concentration samadhi and put that stone under their tongue and they can get all the nutrients from it.

The most advanced one is getting nutrients from air. You just inhale air and you can survive. Lama Konchog practiced this, so he didn’t have to eat anything. He just inhaled air and was able to survive. In one way it seems unbelievable, and in another way, there are such practitioners. In the past, many other practitioners must have practiced like that. In the scripture it shows this, Lama Konchog, during our lifetime, is one who displayed all of those.

He didn’t have to eat anything. He just inhaled air and was able to survive.

Geshe Tenzin Zopa’s Motivation for Becoming a Monk

Back to my childhood, the monks and nuns would come to my family home to perform pujas. They used lots of instruments, like the longhorn, trumpet, bell, and symbol. The chanting was with a lot of tune, I didn’t understand it but anyone would enjoy this melody. I used to feel so much peace, usually during the puja period. My job was to clean, serve tea, serve meals, and wash dishes.

The mountain monks and nuns would come with big smiles and lots of talking, in my family we were so tense and quiet, and when my dad talked we had to be quiet. But when the monks and nuns came, there was lots of laughing and teasing. Then they would go to the shrine room and sing songs, which were actually prayers, but when I was young I thought they were just singing.

By lunchtime, the best food was served for them, and I knew how much hardship it was to get that food; we slept in the rain, and in hot weather, my father had to beg to exchange herbs for rice. They would lick the plates, but after the meals, I would still go and try to find one grain of rice while I was cleaning. I thought it was so unbelievable, even though there was no taste, but just the preciousness, I felt it was so special. Even the sweet tea that they drank completely, I would try to find any drop there before I washed it. Even a little taste felt so amazing.

My father used to buy little orange candies, which were delicious and cheap, and he used to give it to all the kids expect for me, and this built an attachment for me. I used to think if I want to be happy and if I want to eat rice and taste sugar, then I should become a monk. That’s the actual inspiration of why I became a monk and why I chose this kind of life.

I used to think if I want to be happy and if I want to eat rice and taste sugar, then I should become a monk.

Actually, there’s a movie about it that some students from New York made. They have their own interesting stories and some are similar to mine, of conflicts with family or partners or friends. But through my teachings and spending time with me, they felt like they could let go, feel consoled, and they feel benefited.

So one day, they asked me how I became a monk. They said, You carry so many blessings, you must be someone very special to be here. Many great masters can trace back their previous lives. They said, You must be somebody because there are so many lamas, and we listen to many people, but after spending time with you our lives are transformed. They asked who are you?

I said, I may be even more ordinary than you. I have no idea who I was in past lives, I’m not like the special lamas, I’m a monk, but I became a monk from an ordinary motivation, nothing about enlightening sentient beings. I simply wanted to eat rice, taste sweetness, and be happy. The students felt touched and they said, This is something very interesting and down to earth.

I simply wanted to eat rice, taste sweetness, and be happy.

Everything depends on your mind

When you became a monk, you usually shave all hair. And my skull had a big divet in the middle from the rope—you can imagine this seven-year-old boy carrying 10 kilos from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., nonstop. After I shaved, my master, Geshe Lama Konchog, would go over to my head and touch it, and he’d say, The kindest person in your life is your father. It used to make me so angry, but I could not express that to him.

He knew my family, my mother and my aunties were the most loving, not my father. So why did he say my father’s name, who is the worst person, who made me suffer? He never explained to me, I never dared to asked, it took about three years, but the more he’d do that, the more angry I’d get.

Suddenly, my father appeared after three years of not seeing him, and at that time my master was somewhere else. I wanted to impress him, I was longing for just one hug from him and for eye-to-eye contact, for him to see me.

I saw him from the gate, from the second floor you can see straight to the main gate. I immediately ran into the kitchen, we had one Nepali cook and I told the cook, When you see my father can you bring him to my Lama’s room? In his room, I brought his table next to the bed, as if it were my bed, and I brought all his books and texts, and I opened the door. I wanted him to see that I was studying so much, I know so much. But I was just pretending that I was reading.

He got to the door, saw me, I could sense him, he was there for five minutes observing me, then he finally came in, and he didn’t look at me, he looked at the texts, then he said, “I’m very proud of you” and he still didn’t give me a full hug, it was a side hug. Then he left.

After that, I felt happy but still incomplete and empty. I was happy because after three years I got to see him, and at least he said he was proud of me. But at the same time, he still didn’t look at me or hug me. But then three hours later he came back with a very colorful, soft blanket with flowers.

He didn’t even sit down, he just gave it to me, and said, This is for you. Then he says, You’re very lucky, I’m very proud of you, you just follow your Grandpa Lama, I’m very happy for you. But he still didn’t give me a hug, and deep in my heart I was still longing for that, then he left.

When I became a monk, my master told my father that I was still his son, so he had to make the first robe for me so that it was auspicious. When he made the robe, he made it from nylon—all these ropes—and made it very big. But that blanket was his real gift to me. I realized then that whatever money he made in Kathmandu this time from selling the herbs, he probably spent all the money on the blanket. I’m quite sure he went home empty-handed. I could relate to that. I felt touched but incomplete.

Then three years later I got the news that he had passed away, and I felt completely empty, a complete void of a solid figure in my life. I ran into my room, I was saving money in a piggy bank to go home to see my mother, and I broke the piggy bank and brought all the coins to the gompa keeper. He became a monk when he was 40 or 50, and before he became a monk he had children, he had renounced his family, so he knew how to take care of kids.

I went straight to him and held his leg and cried, saying that my father had passed away. I said I wanted to do something for my father, that I wanted to offer light, so he gave me a butter light. During that time, the gompa was small and the biggest holy object was Lama Yeshe’s stupa. I put the light in front of the stupa and cried so much.

Then I realized all the goodness I had, my master, my friends in the monastery. When I first came to the monastery, it felt like a pure land. I didn’t know what pure land was, but now that I think about it, it was exactly like that. I was really liberated from all the suffering.

There, I understood why my master was said, The kindest person in your life is your father. Because of his treatment, I could renounce my family life and home, and dedicate my life to the monastery. By then we were also meeting foreigners, like Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Lama Konchog, and they looked amazing, and you felt happy to just see them.

All of this was due to his kindness. Even today, being able to come here to Santa Fe, to meet the Dharma brothers and sisters, to share my dharma, and life becoming so meaningful, all of it goes back to my father. It was because of him that I got all the goodness in my life and was able to go away from the suffering. My brother, his favorite, is taking care of the legacy and family, and it is a really hard life.

I realized good and bad is all about your perception, nothing substantially exists on the object side, like how we say samsara and nirvana, there is no substantial existence of it, it’s all your mind. If your mind is purified, the samsara land also becomes pure land. There isn’t a pure land somewhere else that you have to travel to, it’s right in your mind.

If your mind is purified, the samsara land also becomes pure land.

Even if you live in the most comfortable place, but your mind is not purified, it’s a miserable place. I came to the understanding that my father was the kindest person in my life; he was actually my first guru. He taught me that everything depends on your mind, and your perception. If you can change your perception, everything can become positive and pure.

Even if you live in the most comfortable place, but your mind is not purified, it’s a miserable place.

When I shared that with these students and the filmmaker, he said we must have a movie about it to share this message. There are so many people going through relationship difficulties, with fathers and mothers, this and that, and some people live with that grudge their whole life, and they think the problem lies in the object.

My experience shows that when your mind changes, everything can change. Because of that they filmed this movie, and I believe the name of the movie is The Monk in the Rice, but they may change the name. After Santa Fe, where we are now, I will go to New York, and spend three days for the final part.

Mental Health & Buddhism

In my childhood, I had mental health problems. Mainly due to circumstances, it wasn’t inborn. The masters would always remind us of the unbelievable Buddha potential we all have.

If you aspire to be Buddha, you can be Buddha. Aspire to be happy, you can be fully happy. Aspire to serve others, you can serve others. It doesn’t matter your background, or whatever history you may have, those are circumstantial, temporary obstacles. Your ultimate being is so pure and equal to everybody, even to the Buddha.

If you aspire to be Buddha, you can be Buddha.

As long as there’s a constant virtuous environment—and you diligently learn and practice, purify those negative thoughts and accumulate virtuous imprints—you can be completely transformed from the unhappiest person to the happiest person. From unvirtuous to virtuous. From nonspiritual to spiritual.

I experienced that immediately, within a day, the day before I arrived to Kopan Monastery, everything was miserable. Everywhere was miserable, that was the worst period. But the moment I entered the gate, every goodness started, right there I felt happy, it felt like pure land, even though I didn’t know the description.

I remember when I entered the gate with my master, in Kopan at that time there were two big dogs, one was called Macala (the protector), he was dark and huge, and the other was brown, called Gomshen (the great meditator). Lama Yeshe brought them as puppies from Tibet.

Macala was huge, bigger than me when I was nine, and he jumped on me like he wanted to bite me, but he didn’t. He pushed me to the ground and I almost lost my consciousness, because for me this dog was like a tiger. Then, when my master pulled me up, he told me Macala had changed my life, he had removed obstacles. He was the protector, he was not an ordinary dog. My master said, You will succeed in your spiritual journey.

Then due to changes of weather, changes of places, and a bit of fear from the dog, I was sick for three months with heavy diarrhea. There I experienced what unconditional love means. I was living with the late Abbott and Geshe Lama Konchog and I was completely bedridden; I couldn’t control my bowels and I would vomit everywhere. My masters would clean me, take me to the toilet, shower me, and literally cleaned me by hand.

There I experienced what unconditional love means.

I’m sure my mom did that when I was a baby, but I don’t remember. I didn’t really experience that at home, but I experienced that with my two masters. They were so gentle and loving, they were very soft, they’d feed me with a little spoon. Overtime, I saw these masters do the same for the other children there.

Like many others, I said I was an orphan, even though I have my father and mother, but in an emotional sense you are an orphan, and they are taking care of you like that. All of this heals you, all of this can heal any emotional crisis, any mental suffering.

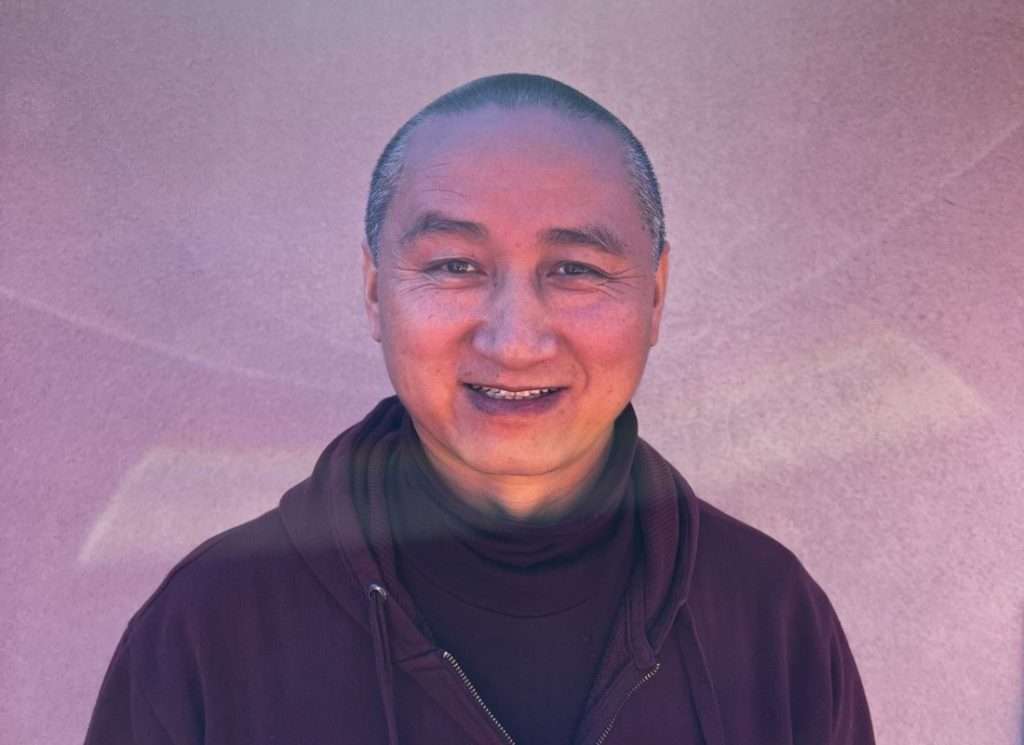

Now I am always happy, and it is a sustainable happiness. I’m sure all the spiritual teachings have the same impact, a genuine sense of unconditional love, compassion, kindness, and gentleness, this is the real medicine to heal any mental sufferings.

Now I am always happy, and it is a sustainable happiness.

Then if there’s an element of our past karma, Buddhists believe that everything you go through, good or bad, has an element of past lives accumulation. This practice is still the main antidote, the Buddha Dharma is built on these basic values of love and compassion. This is what I experience and try to practice and share with others.

I always try to translate everything into a day-to-day guide to make you a better human being, more positive, and direct antidote to an unhappy life and mind, negativities. Then you can enjoy life full of virtues. If you live a life full of love, then you are living a virtuous life.

If you live a life full of love, then you are living a virtuous life.

If you are unable to serve others, express love and compassion, then this human life is meaningless. You can be very rich, famous, with high status, but missing this element, not being at the service of others and being unable to express compassion, then it is meaningless. The real cause of joy and happiness comes from that.

If you are unable to serve others, express love and compassion, then this human life is meaningless.

In the past 20 years, I’ve traveled to many European countries, America, Southeast Asian countries, I’ve met all sorts of people, from little kids to seniors, and the emotional crisis is very common. There is so much unhappiness.

Even in the study of Dharma, if you can’t translate things to be sensible to your mind and emotion, then how much information you collect will not help. I see people who have been studying Buddhism for 30 to 40 years, but they are so angry, unhappy, and impatient. They’ve met unbelievable masters, but the motivation must be wrong.

I see people who have been studying Buddhism for 30 to 40 years, but they are so angry, unhappy, and impatient.

There is basic criteria to receive the full benefit of this Dharma practice in Buddhism, the quality of student. There are three qualities: nonpartisan, diligent, and basic wisdom. Nonpartisan, when you practice Dharma it’s not for holy benefit, it’s for ultimate liberation from negative emotions and karma. To develop wisdom, attitudes like loving-kindness and compassion. It is not just collecting information. Some people just collect info and think that will transform you.

Many of the teachings lack the elements of gentleness, loving, and humanness, and it is only based on the philosophy. Even in a normal school, little kids experience serious depressions and emotional crises. On top of whether you are learning Dharma knowledge, you need the basic human values of love and compassion, and sharing that human to human.

As I mentioned before, I was greatly benefitted by these gurus, like Lama Konchog, with their love, affection, kindness, gentleness, I think that is the key that healed me. An emotional crisis can be huge, but looking at my journey, it was very intense, very serious and I was able to heal right there. At that time I wasn’t even exposed to the philosophy or extensive learning, I was just exposed to the human love, care, and compassion.

Interview conducted by Isabela Acebal

Our resident teacher, Geshe Thubten Sherab, is joined by

a team of some thirty FPMT and other teachers,

facilitators, and meditation leaders from around the

world.

Our resident teacher, Geshe Thubten Sherab, is joined by

a team of some thirty FPMT and other teachers,

facilitators, and meditation leaders from around the

world.